William Hume Blake (1809‒1870) was the first Blake to come to the Charlevoix region. Born into an influential family in Ireland, he settled in Toronto, where he held important positions as a lawyer, politician and judge. He discovered the Charlevoix while he was stationed in Québec as the Solicitor General of Upper Canada during& the 1850s. He often stayed in Chamard’s Lorne House at Pointe-au-Pic.

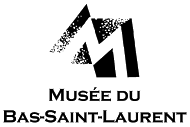

After his death, Blake’s two sons built their own summer home at Pointe-au-Pic. Edward, lawyer and politician in the Liberal party, built the Red House in 1874. During the same period, Samuel built Mille Roches, shown in this photograph. Edward’s and Samuel’s families were accustomed to the steamer trip from Toronto to La Malbaie, then called Murray Bay.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Mackenzie coll.

The Blakes played an active role in Canada’s growth, both in law and politics. They personified the Liberal tradition that prevailed in the summer colony of Malbaie. For example, Edward Blake was Premier of Ontario (1871) and leader of the federal Liberal Party (1880‒1882).

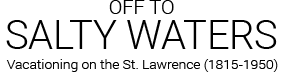

Born in 1861, Samuel’s son was named for his grandfather, William Hume Blake. Like his forebears, William studied and practised law in Toronto, and Charlevoix was also dear to his heart. He differed from them, however, by his lack of interest in political debate, preferring instead to outwit the trout!

The writings of William Hume Blake (In a Fishing Country, Brown Waters) sung the virtues of the Charlevoix countryside, its inhabitants and, above all, its lakes, rivers and fish. He was also the first translator of Louis Hémon’s celebrated novel Maria Chapdelaine.

The photograph above shows William Hume Blake in his fishing gear, smoking his ubiquitous pipe (indispensable for keeping the mosquitoes away!)

© Musée de Charlevoix, Mackenzie coll.

When William Hume Blake was young in the 1860s and 70s, summer holidayers in the Charlevoix were mainly upper-class English-speakers from Quebec and Ontario. They sought rest and time with family in a charming, peaceful environment.

Americans began to come for their summer holidays in great numbers from 1882 onward, following on a recommendation of a New York physician. In his In a Fishing Country, Blake complains about the change in summer people’s mentality, as they tried to recreate city life in the country.

The arrival of the golf and tennis fans in the 1890s hardly reassured our fisherman! He did admit, however, that these sports offered new leisure opportunities to women, who were often left alone during the summer holidays.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Elizabeth Bacque coll.

Fishing and hunting expeditions were opportunities ;to get away from work and daily cares, but also away from “respectable” cronies who didn’t like to get their hands dirty! Mosquitoes, the discomfort of sleeping in tents and the challenges of stalking game or fish weren’t for everyone!

William Hume Blake eloquently described the mood of these expeditions. While they did not always stay in a tent or camp as comfortable as those reserved for the sportsmen who hired them, the guides played an indispensable and well-appreciated role. They actively planned the day’s activities in the forest and, once their duties fulfilled, guides would hunt or fish alongside their employers, silently sharing the same love for this sport and for life in nature.

At the end of the 19th century, wives would occasionally accompany their husbands on these expeditions, and not only as observers. Many old photographs show them hunting or fishing alongside their men.

William can be seen in the centre of this photograph and his wife on the right.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Mackenzie coll.

William Hume Blake forged the way for other sportsmen who explored every inch of Charlevoix. He co-founded La Roche Fishing and Hunting Club in 1890, and was closely involved in creating the Parc national des Laurentides in 1895. This territory covered the present-day Réserve faunique des Laurentides and the Jacques-Cartier and Grands-Jardins national parks.

In his books, Blake denounced the impacts of poaching and logging on wildlife but, most of all, he praised the backcountry in his tales that featured nature, fishermen, guides and forest rangers as their main characters.

This photograph shows the La Galette camp in the village of Saint-Urbain and the means of transportation used to negotiate the rough roads that led there

© Musée de Charlevoix, Mackenzie coll.

William Hume Blake spoke French very well. Over the years, he became close with many Charlevoix residents, including guides and farmers. He often expressed his admiration for their physical prowess, knowledge of the land and skill, for example, in making or repairing canoes or building temporary bridges.

In this photograph, we see Métis guide Nicolas Aubin repairing a canoe at the end of the 19th century.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Deux cent ans de villégiature dans Charlevoix coll.

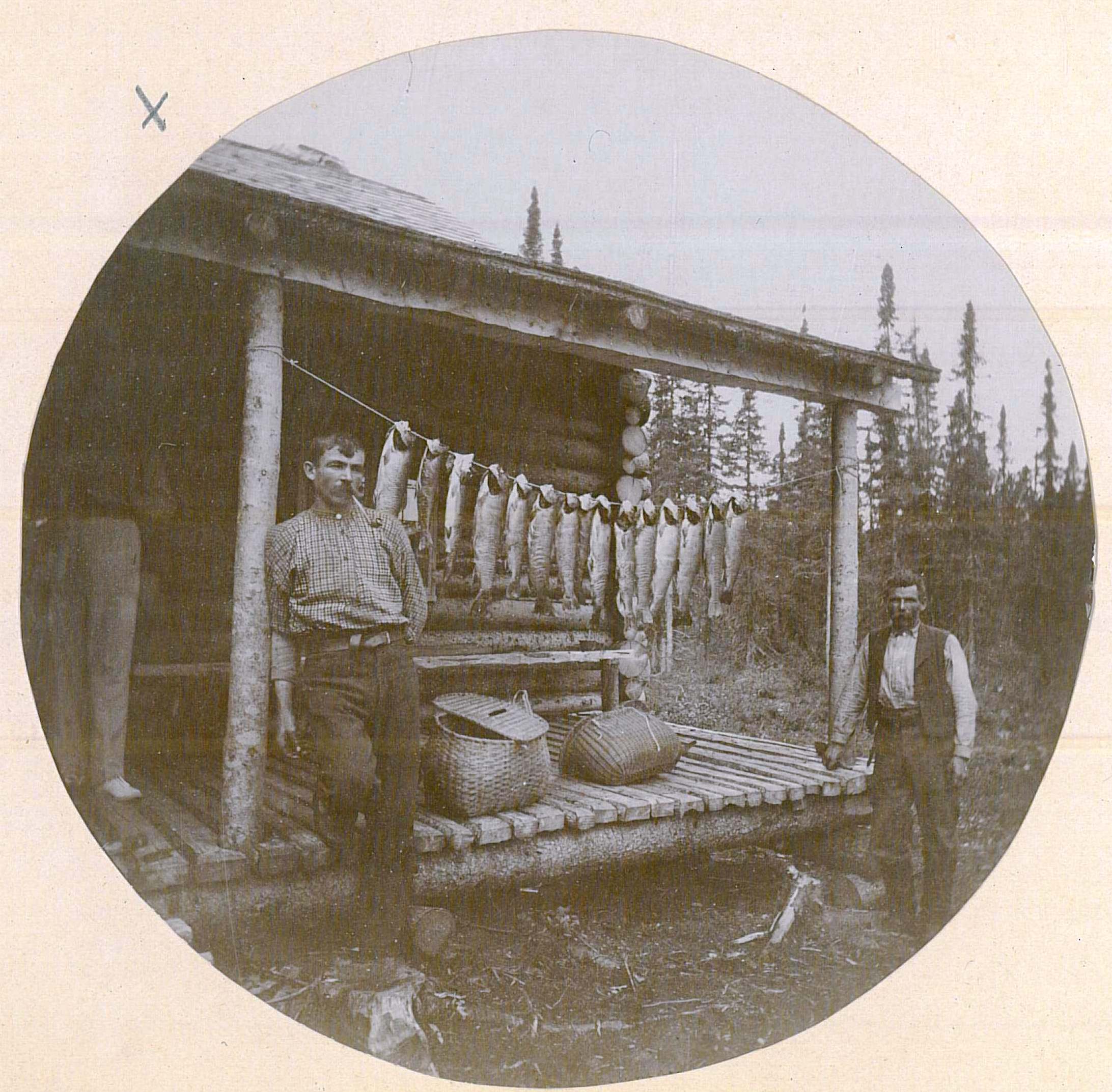

A fisherman might catch several dozen trout in a day of fishing. Wasting any of this fish was not tolerated. The guides taught William Hume Blake to dry his catch over a fire. Depending on the length of the smoking and subsequent storage, the trout could be preserved for a few weeks or months.

Here is a photograph of the guide Thomas Fortin from Saint-Urbain and his son, Thomas-Louis.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Mackenzie coll.

Beginning in 1915, dynamiting along the St. Lawrence for the railroad disfigured the places summer residents frequented. William Hume Blake and many other summer residents wondered if Charlevoix would lose its charm to the inevitable arrival of modernity.

Taken in 1906, this photograph shows William and his wife near Cap Blanc in Pointe-au-Pic (La Malbaie). Their daughter Helen married Philip Mackenzie, and their descendants are still among the Charlevoix’s most loyal visitors.

William Hume Blake died in 1924. His funeral was held at the Protestant church in La Malbaie. Among the pallbearers were some of the guides with whom he had shared so many adventures over the years.

© Musée de Charlevoix, Roland Gagné coll.